One aspect of this story, Leon says, will be showcasing Kurdistan as a “crossroads of ancient civilisations.” Without erasing the ethnic tensions that still trouble Kurdistan, and without taking a political stance, those involved in the trail wish to see the remarkable cultural heritage along the trail’s 220km corridor as something to showcase.

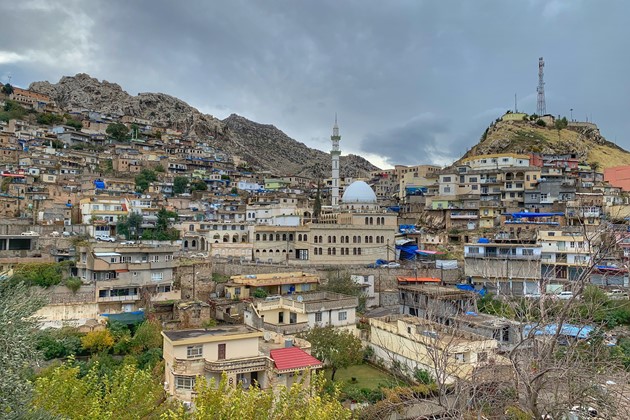

“We have the Assyrians at the start, and we pass through the Yazidi’s holy place at Lalish shortly afterwards,” Leon outlines. “Then, in a village called Shush, there are the remains of an old synagogue. There was once a large Jewish population, before all the Jews in Kurdistan fled decades ago, but there is still that memory of a point they were still there. There are Sufi mystics in a town called Akre. We have some Mandaeans. We've got the Zoroastrians further to the east.”

A more pressing narrative, though, is the emergent story of Kurdistan as a place of peace. There is a saying in Kurdistan, Leon says: “the Kurds have no friends but the mountains.” For years, the mountains have provided refuge for Kurdish people. Some of the trail’s local guides, stakeholders and villagers were Peshmerga (the Kurdish armed forces) fighting against both Saddam Hussein’s forces and the Islamic State. Many have lived in the mountains for months or years at a time. “A lot of them have got very moving and impactful stories to tell,” says Leon.