After turning professional but becoming disillusioned with aspects of snowboard culture, her artistic practice helped her reconnect with her Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw heritage and reframe her relationship with snowboarding and the mountains. Our Editor Sam spoke with her about this journey and its implications for the stories we tell about snow sports.

Alert Bay, a village on Cormorant Island off the northern coast of Vancouver Island, gazes down Johnstone Strait beneath British Columbia’s towering Coast Mountains. It is a place of wilderness, whales, salmon fishing and rich Kwakwaka’wakw heritage. Originally a ‘Namgis burial ground, today’s population is half First Nations and half people of European descent. Many families there, including Meghann’s, have deep roots. “It’s a beautiful place,” she concludes at the start of our conversation.

In this environment Megahnn grew up skiing and snowboarding on nearby Mount Cain. A snowboarding career became a clear ambition as she pursued boardercross, giant slalom and halfpipe through school with the support of her dad Brian. By eighteen she was sponsored, navigating a culture of travel budgets, film parts and competitions on her way to the top of the sport. “There was one point during one of my later seasons where I was riding with a lot of the people that I have looked up to and respected,” she remembers. “That was pretty incredible.”

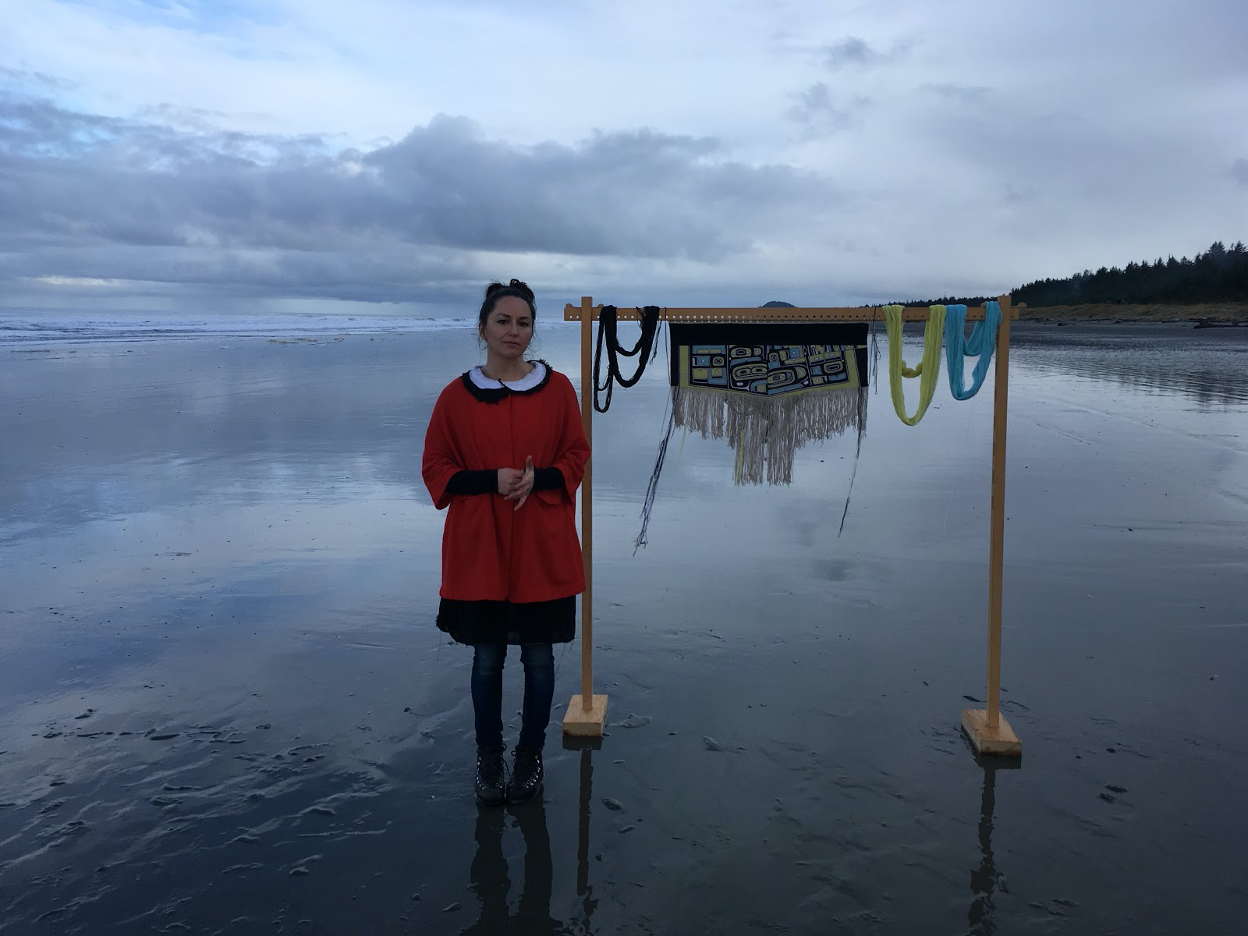

Photos courtesy of Meghann O'Brien

The life Meghann describes - riding success and time in the mountains - will sound dreamlike to many. “I was spending so much time at that alpine level one year,” she recalls. “You go from frozen lake bed to frozen lake bed. It’s just this endless layer in the mountain range, like the second layer of Earth... I really love being in that environment.”

But snowboarding success comes with pressures, which for Meghann led to a partial disillusionment with snowboarding and a journey that demonstrates the power of renewed cultural frames in helping us change how we think about not just adventure, but life.

Meghann’s disillusionment was rooted in commercial forces. “The pressure to produce is strong,” she explains. “I found with that mentality - when you're in the backcountry to get shots - you lose focus of the bigger picture. For me it was really difficult to be able to enjoy the space and appreciate the space. It was just a singular focus on building a video part, on what tricks you have, what you want to do, where you want to build and how it's going to look in a photograph and a subtle competition with other groups that are filming.”

This dissatisfaction deepened when Meghann became interested in weaving in 2007. Although much of the coverage she was receiving focused on her art and Indigenous heritage, sponsors seemed relatively uninterested - unable to see a bigger picture beyond technical snowboarding progression. She decided to take some time out to focus on her art.

Photo courtesy of Meghann O'Brien

There is no sense of complaint in how Meghann talks about this shift, but an awareness of what is at stake when we allow money to mediate culture, including ideas about what ‘progress’ looks like. As well as detaching us from our environments, commercial forces can equate personal value and profit in unhealthy ways. The length of a rider’s video part, for example, is sometimes determined by how much their sponsor has contributed, Meghann says. “It was a funny thing,” she reflects. “It's very enticing for brands.” She adds that she knows many talented snowboarders who have fallen out of love with snowboarding under the pressure, and by the time they have managed to find the love again while still producing, the industry tends to want them to move on.

The implications here go beyond the stress levels of elite athletes and into the question of what outdoor culture might look like if rooted in different values, different stories. This possibility emerges when Meghann discusses her artistic practice, which centres around weaving with hand-collected materials - especially cedar bark, for baskets, and mountain goat wool, for blankets - with significance to her Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw heritage.

Learning to weave was a powerful experience for Meghann. Compared with snowboarding, which felt like an egotistical attempt to live up to a certain image, her art was “much more focused on community and family, and felt like it tied into something that was really important that it be in the world.”

“Aspects, through my teachers, related to other families and community members,” she says. “Then you start getting into weaving the regalia of wool, and those go with songs and dances. You end up embedded back into the ceremonial aspects of the culture.” Ultimately, building her artistic practice gave Meghann “a connection to the culture that I hadn't ever had. There is the intellectual knowing of what it is you’re doing, and then there is really experiencing and feeling it on this really deep level.”

Photo courtesy of Meghann O'Brien

She invokes the image of a tree of life to describe the rooted nature of her Indigenous artwork. “The base of the tree and the trunk and the limbs stay there through all of time relatively, slowly expanding and growing,” she explains. “The art forms that are expressed by people from our culture are almost like the flowering or the fruit on the tree.” These art forms, in turn, become seeds.

Indigenous cultures in the Pacific Northwest, Meghann explains, have no word for ‘art’, because they have no conception of objects of art as somehow detached from life, as is prevalent in Western culture. “Our whole world was this beautiful expression, and had so much meaning. The meaning wasn't just the object; the meaning was also the layers of experience of that object.”

This perspective has led to challenges. It has been a struggle, Meghann says, for First Nations communities to have their art accepted as art, rather than ethnography. But her metaphor captures a holistic view of culture that has helped transform her own perception of snowboarding, and contains insights for a wider reframing of outdoor culture.

Photo courtesy of Meghann O'Brien

After a year away from snowboarding, Meghann returned with a renewed appreciation for the mountains. “Working with mountain goat wool, I was able to consider the mountains from another perspective, which was some of the stories that are in our culture and some of the spiritual beliefs about mountains,” she explains. She has since found herself more able to carry “some of that into the mountains with [me], and being less involved in ‘What can I do in the mountains’ and more in ‘How is this tool of snowboarding, or skiing and splitboarding, able to bring me into a space that is really otherworldly?’”

At the heart of this reframing is a more thoughtful approach to the connection between a thing and its place, or origin - whether between an object and its source or a snowboarder and her environment. Consumer culture too often encourages connections rooted in convenience, cost savings and taking what we want rather than what we need. But as with her artistic work, Meghann’s perspective on snowboarding now cherishes a deeper, more thoughtful sense of connection.

Being more intentional in this way is not simply a privilege of the rich, Meghann argues. It can be about things that are “just well made by a single human being paid a living wage.” In a similar vein, she continues, “something I really want to emphasise … is whether you’re doing it as a professional or for fun, it’s still snowboarding and it still feels the same. I think it’s way cooler when I see people that have just made it a part of their lives and are enjoying it.”

“Why does this success even matter?” she continues, referencing the pressure to perform at the heart of snowboarding (and much adventure) culture. “Why is that of value to anybody? Maybe you are some idealised version of what a human can be. We like to hold people up on pedestals, but being good at a thing shouldn't be important, I don't think. I’ve been thinking about that about artwork as well: that the superficial finished product is what's valued, but how does that piece contribute to the world? How is it helping the community out?”

Meghann does see promising signs in how the snowsports industry is telling new stories about the values underpinning snowboarding. She points to Marie-France Roy’s The Little Things, a film project spotlighting environmentally conscious riders, as a particular influence.

“It seemed to me that companies wanted to promote this big party mentality, or just the rock star image,” she says of the industry when she was professional. But now “there has become people who are in the spotlight that are a lot more grounded in the way they are represented and carry and live out their lives. It's not all about flying all over the world, you know, without any concern for anything.”

Meghann’s experience is personal but shows the possibilities in telling new stories about adventure culture. The question of how the adventure community can find new cultural references to help with this task runs through her story. Her answers - art, and her Indigenous heritage - are compelling not just because they are true to her, but because they offer the wider adventure community a thought-provoking example of new story weaving.

Photo courtesy of Meghann O'Brien

You can learn more about Meghann’s work at her website, and follow her on Instagram at meghaanobrien.

References and recommendations from our conversation:

- Contraddiction - A snowboard film that follows snowboarder Elias Elhardt in questioning how compatible snowboarding is with an ecologically responsible life.

- The Little Things - a 2014 snowboard film focusing on environmentally aware snowboarders.

- Treeline - A Patagonia-produced ski film that explores the connection between humans and trees.

- The Ingenuity Gap - A book by Thomas Homer-Dixon exploring the gap between our need for ideas to solve complex problems and our actual supply of those ideas in an increasingly complicated world.

- Beyond Boarding - A creative collective in the Pacific Northwest whose projects span films, youth programs and direct action, all with a dedication to outdoor culture, environmental education and social justice. Meghann is featured in their 2018 film, The Radicals

- SUNŌKERU - a short film produced by KORUA Shapes following a snowboard crew (including Meghann’s sister, Spencer O’Brien, also an Olympic snowboarder) riding the famous powder of Hokkaido, Japan.