The Northern Meadows, one of the last wild spaces in Cardiff, is under threat from a multi-million-pound development. In this climate- and Covid-anxious age, Sophie Standen talks to the urban Cardiff community campaigning to save the Meadows.

The Northern Meadows, one of the last wild spaces in Cardiff, is under threat from a multi-million-pound development. In this climate- and Covid-anxious age, Sophie Standen talks to the urban Cardiff community campaigning to save the Meadows.

The Northern Meadows, as affectionately known by locals, are snugly nestled in the rolling hills of Northern Cardiff. They are surrounded by one of Europe’s largest roundabouts, the river Taff, a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and the Cardiff suburbs of Whitchurch and Coryton. This 23-acre site is under threat of development, meaning that one of the last green spaces in Cardiff will now disappear.

In the face of enormous pressure to treat increasing cancer rates in Wales, this meadow and woodland will soon become the site of an approximately £700 million cancer centre, conference centre and 700-space car park.

This is yet another David vs. Goliath story, as seen in many places across the UK, whereby a local community opposes a development imposed on them by authorities. Yet, proponents of the cancer centre and authorities state that there is no other choice but to build on this site, and that the current 63-year-old cancer centre is simply not fit for purpose to deal with projected cancer rates in South Wales.

Photo credit: Sophie Standen

This is something that people who are part of the approximately 3,000-person campaign to Save the Northern Meadows don’t dispute. All wish to see better cancer services in South Wales. They do, however, dispute its proposed location, and the destruction of the dwindling green space that will accompany it. They further question the model of the cancer centre, on which 163 clinicians have written a formal letter to the government stating that the development would provide sub-standard cancer care.

Cardiff only includes 8% green space, one of the lowest amounts in cities across the UK. Some campaigners argue that there are many more, better, brownfield sites in Cardiff where the cancer centre could be built, including a currently defunct, empty psychiatric hospital which neighbours the Meadows. Others say that it should be built adjacent to University Hospital Wales, so that patients can receive the best care.

In an age defined by Covid-19, as well as increasing threats of flooding due to climate change in South Wales, local people wish to keep this green space wild. They value it now, as a place to explore and ‘be’ with nature, let alone as a place to protect their houses from the ravages of the River Taff’s floodwaters.

In spite of the threat to homes and the environment, and a questionable clinical model, successive planning permissions have still been driven through by Cardiff Council and the Welsh Government. This has caused ordinary people, who had never previously considered themselves to be activists, to come together to fight for this green space in creative and interesting ways.

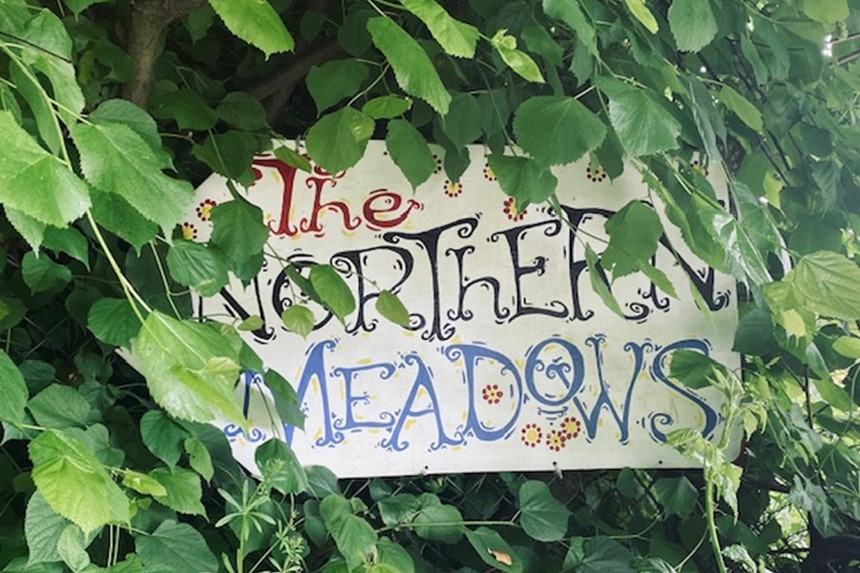

Save the Northern Meadows stickers where part of the development is due to take place. Credit: Sophie Standen

Save the Northern Meadows signs where part of the development is due to take place. Credit: Sophie Standen

Michelle Gough, a child-minder, has lived in this area of Cardiff all of her life and feels a deep sense of connection to the Northern Meadows. She describes her grandmother taking her to the Meadows when she was little, saying that “from a family point of view, we’ve been enjoying this place for 100 years.” She explains how she has never really been involved in protests before and has always been worried about breaking the rules. However, she says this campaign to save the Meadows is “too important because there’s hardly any places left around Cardiff like this”.

“I’ve always enjoyed this place,” she says. “I was brought up here as a child and learnt about the birds, trees and flowers, and my children have been able to enjoy this place. And now I’m child-minding, so those children are able to come too.”

Michelle says that throughout Covid, the space became “invaluable” as her husband needed to shield and found that there were too many other people walking around the parks in Cardiff. She found that the positive of Covid was “appreciating what’s close” as you “couldn’t get in the car and drive to the beach”.

Being part of the campaign has definitely pushed Michelle out of her comfort zone. “Knocking on people’s doors, setting up stands and camping” have all been a learning experience.

Throughout the past few months, Michelle and others have been camping out at the Meadows some weekends. She says doing this has brought her “a lot closer to nature, and being outdoors made me appreciate what is right here, a few minutes walk away”.

Michelle adds that prior to campaigning, she had never camped on the Meadows before. This was because she only felt safe doing so as part of a group, and was unsure if she was allowed to camp there. However she has camped out a few times since joining the campaign, and really enjoys being able to camp in a city and be closer to nature, especially so close to home.

From being someone who had “never really felt the need to protest,” Michelle now says that “in an ideal world, I would give up my day job and I would be up in those trees.” Being part of the campaign to save the Northern Meadows is fantastic, she says, because “they’re a great group. You’re often so deflated. You can choose to use the anger in a positive way, and so it drives you to put more posters up and post more leaflets.” Michelle continues: “There’s a perception that we have a lot of green in Cardiff, but we don’t, it’s actually not very good”

'In an ideal world, I would give up my day job and I would be up in those trees.'

Cat Lewis, a local artist who lives next to the Meadows, echoes this sentiment. She is part of a community in the Hollybush Estate, where 500 or so residents do not have access to gardens. She has also been a key part of the campaign to save the Northern Meadows.

After Cat got diagnosed with cancer in 2019, she was given a flat by the council, so that she could receive treatment at the current Velindre Cancer Centre nearby. She soon started using the Meadows. “It’s almost like wild fields over there,” she says. “You don’t feel like you are in Cardiff.” She also mentions that the Meadows have been vital for her mental health. “People use this piece of land, people use it and walk on it and it’s wonderful for the environment here.”

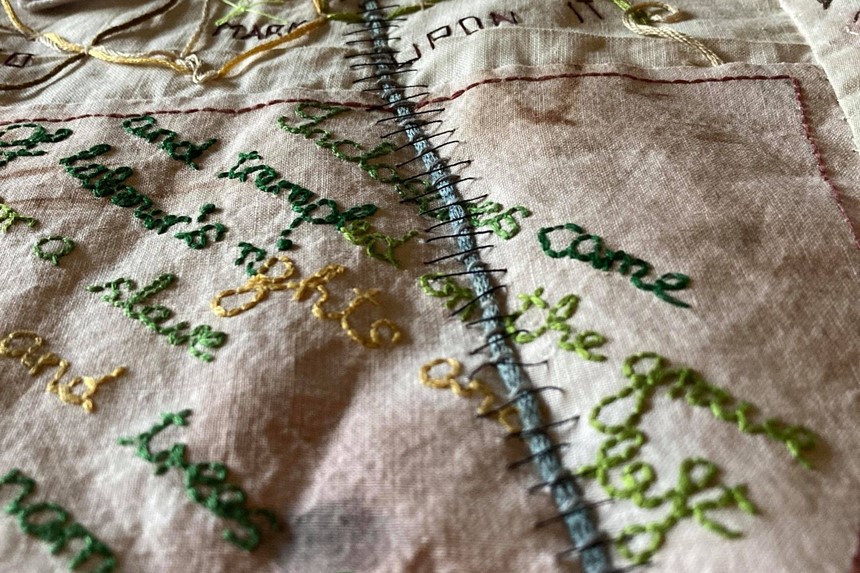

A key part of Cat’s artwork is nature and sustainability, and she often draws on the Meadows for materials and inspiration. Throughout lockdown, she began a community project which aimed to draw on a people’s history of the local area. Inspired by the Tithe maps of Wales, she asked members of the community to embroider a piece of fabric to represent what the Meadows and surrounding areas mean to them. This was to show how the local community conceives of the area, rather than showing what developers value. She then stitched this fabric together to make a quilt. Her work was on display at the Elysium Gallery in Swansea, which depicted alternative ways to protest.

Cat says that she plans for the quilt to be shown in the local library, as she has also “made a book with people’s letters where they wrote about the land, the history and their feelings. So it’s not only a protest piece, but also a part of community history.”

The community quilt made by Cat Lewis: Credit: Cat Lewis

Cat says green space, especially for people who don’t have access to a garden, is more important now than ever. “There’s a lot of people here who can’t go off in a car. People with houses and cars don’t realise that life isn’t like that for everyone."

Part of the problem, she thinks, is historical land use in Wales. "For the past 150 years or so, the land in South Wales has been debased by industry. You can’t expect people to value something that has not been respected. There’s got to be a bigger government-led plan."

Throughout Covid, Cat decided to make a small community garden in front of her flat, transforming it from concrete to something all residents can use. She talks about how the young children love the garden, and loves hearing them say, “Look at the size of the daisies, look at the bees.” She explains: “That’s the grounding of it, doing this so that kids start to appreciate and value nature.”

'For the past 150 years or so, the land in South Wales has been debased by industry. You can’t expect people to value something that has not been respected. There’s got to be a bigger government-led plan.'

A homage to Cardiff’s industrial past. The Meadows were in close proximity to 18th century tinplate works. Credit: Sophie Standen

In 1964, Welsh ornithologist and naturalist Ronald Lockley wrote a book called The Private Life of the Rabbit, based upon countless hours of study of the rabbits that lived in the Northern Meadows. As a child he would spend hours in them, exploring and watching flora and fauna that lived here. His experiences here, and eventually the book, were the basis for the popular children’s book, Watership Down.

Approximately 50 years later, roughly 56 million people across the UK live in urban spaces. In spite of talks surrounding climate change, and the importance of green space for mental health and wellbeing, it still seems that many city and national authorities are not listening to their residents about these issues.

In an effort to challenge this development, the Save the Northern Meadows group, spearheaded by Cat, has recently opened a court case against the Welsh government’s decision to allow this build to go ahead. As Cat concludes, with a smile on her face, “Somebody’s got to do something. We’ll keep fighting it”.

For many children, a grounding in a love of nature, exploration and adventure requires access to green wild spaces. How will we learn to love the outdoors, when there is no outdoors to love?