Clare Qualmann is an artist and researcher working across a wide range of media; from drawing and sculpture to text-works and live art events. Her work often takes the form of walks. Among other projects Clare was a founding member of the Walking Artists Network. She is the co-editor of Ways to Wander, a collection of 54 intriguing ideas for different ways to take a walk. Other projects include walkwalkwalk, Footwork, Perambulator, Spinning Stories and East End Jam.

Claire Hind runs the MA in Theatre and Performance at the School of Performance and Media Production at York St John University. Claire has an international performance practice with artist Gary Winters - together they create dream walks, Super 8mm film, live and visual art influenced by cult cinema, dead icons and dark emotional ballads. Their latest project, Astronomical, created during lockdown, charts a route through the city of York across a year. Along with Clare, she is the co-editor of Ways to Wander, a collection of 54 intriguing ideas for different ways to take a walk.

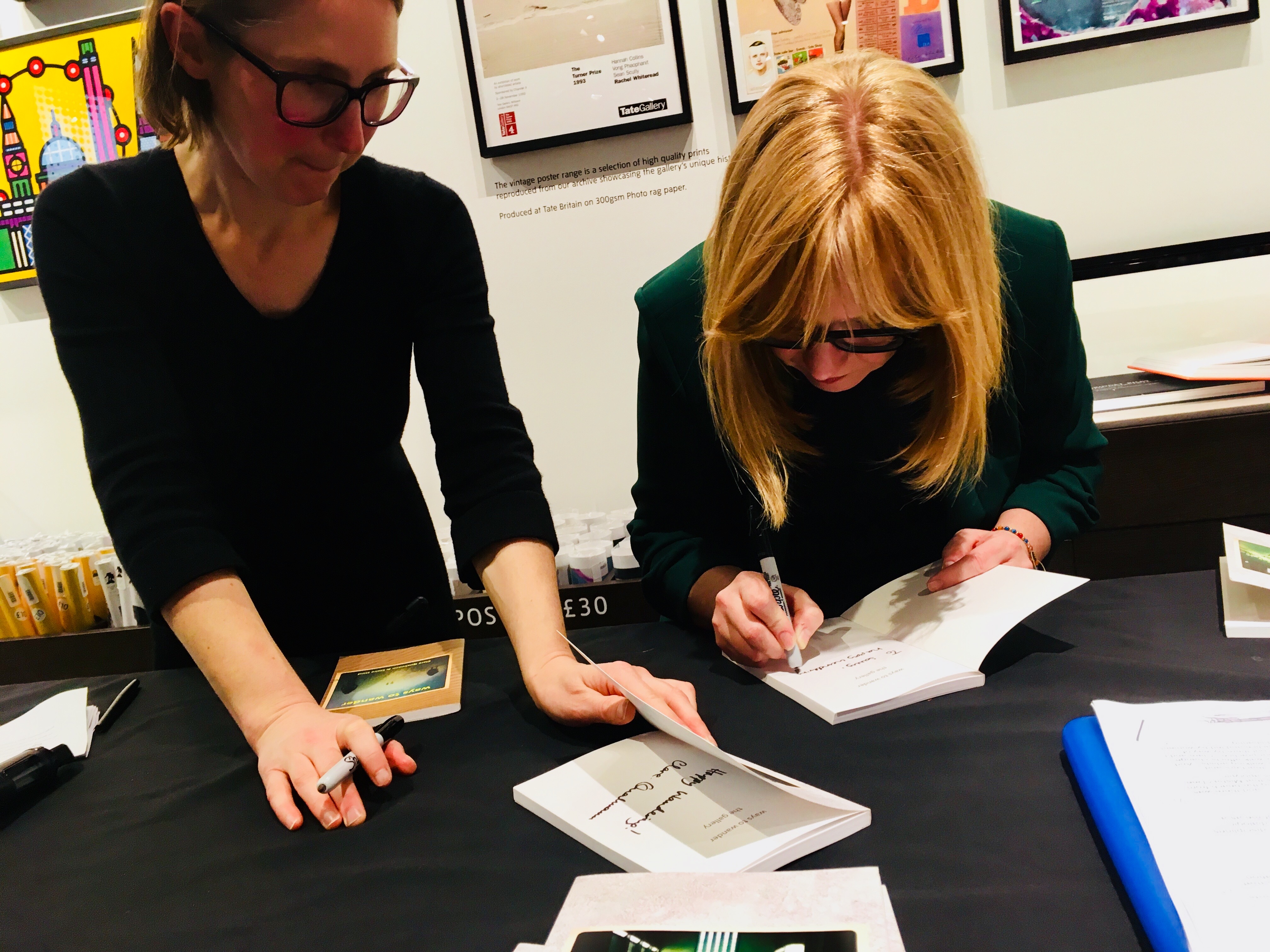

Clare Qualmann (left) and Claire Hind.

What drew you both to walking as a creative practice?

CH: Hiking in the mountains of Wales as a child was a weekly ritual for my family no matter what the weather. I have nostalgia for those walks and retrace them in my mind regularly as performance. My professional practice as a walking artist began because of a childhood dream. I dreamt that a giant gorilla picked me up and carried me away. This dream and the feeling I got from the dream has never left me. I developed this dream into a walking performance with the artist Gary Winters. From here, my walking arts interests deepened and I met Clare Qualmann via the Walking Artists Network.

CQ: I first began using walking in my work as a way to multitask! I was already interested in art and everyday life, and in repetitive performance that related to domestic actions. I was walking to work (in east London) in the late 1990s and early 2000s and thinking a lot about the city, space and creative activity that did not require any permissions or approvals. I began working with other artists on a series of nightwalks that opened up places in the city that otherwise felt unsafe or out of bounds.

How would you describe walking art?

CH: Walking art connects the imagination with an ambulatory journey. Of course, walking art can be many things: a poetic experience, a theatrical meander, a story ramble, a sound-based amble, a political walk, a subversion, an intervention, a game, a meditation, a dedication, a cultural reflection. The experience can vary from solitary wander to a participatory event. Walking art sharpens the senses so we can focus a little more closely and perceptively with our surroundings or be challenged by how surroundings have been planned.

CQ: As art in which the action or experience of walking is inherent. There is a lot of amazing art that is inspired by walking, or that documents walks, but to my mind for a work to be walking art people need to take part (to walk, to move) in it for themselves. It’s durational and experiential.

'Walking art sharpens the senses so we can focus a little more closely and perceptively with our surroundings or be challenged by how surroundings have been planned.'

Are walks adventures? If so, in what sense?

CQ: Yes, they can be! I would say that any walk that has some sense of the unknown, or some elements of exploration within it. That might be in a place that you are quite familiar with, but that you take a different approach to. When I first started working creatively with walking I worked very specifically in my own neighbourhood actively seeking new places and spaces - walking out of my comfort zone. Those were definitely adventures.

CH: An adventure in walking arts might be experienced through its playful attitude to space and place. For example, imagine you are an audience member on a walking performance, and you witness your dream being told by performers on that walk as part of the journey through the snickelways of York. If seen through the lens of an adventure, this walk might bring about arousal not through a high-risk sport, but through an experience of deep play, where you find yourself captivated by the moment in tune with the immediate surroundings. Here, the difference between a dream and reality is uncertain as you wander the city’s alleyways.

To some, the idea of a ‘rule-based’ walk may seem like the very opposite of adventure, which is often considered a thing of freedom and escape. But I sense the book would disagree. If so, why?

CH: There is freedom within constraint. At the beginning of our process when conceiving the book, we put out a Wander Score call for artists to submit a page of instructions but with strict limitations.

A Wander Score refers to each page in the Ways to Wander Book that is scripted as an instruction for someone else to interpret and wander. We named the term. It specifically relates to our interest in Fluxus event scores, and a theatre writing course I run where students score their walking performances in a myriad of spaces as alternative scripts. The Wander Score relates directly to wandering experiences and the limitations we (Claire and Clare) have set as the conditions for the artist to conceive and write/draw their score, in that they have a direct aesthetic consideration between the page and the walk. Such constraints allowed each artist to think more clearly about how to communicate their idea to a wanderer, and to think more deeply and creatively about what a Wander Score could look like on a page.

The concept was to generate original creative material for the page as well as offer walking instruction. The results show that each Wander Score is well contextualised and visually unique. The scores, because of such rules, enable the wanderer to go on the walk with confidence in direct connection to the visual element of the score’s layout.

CQ: Sometimes rules can be the thing that frees you. So, if you are used to navigating with a map, or a phone, or with street signs, and the rule tells you not to do those things, you can end up having a completely different type of adventure.

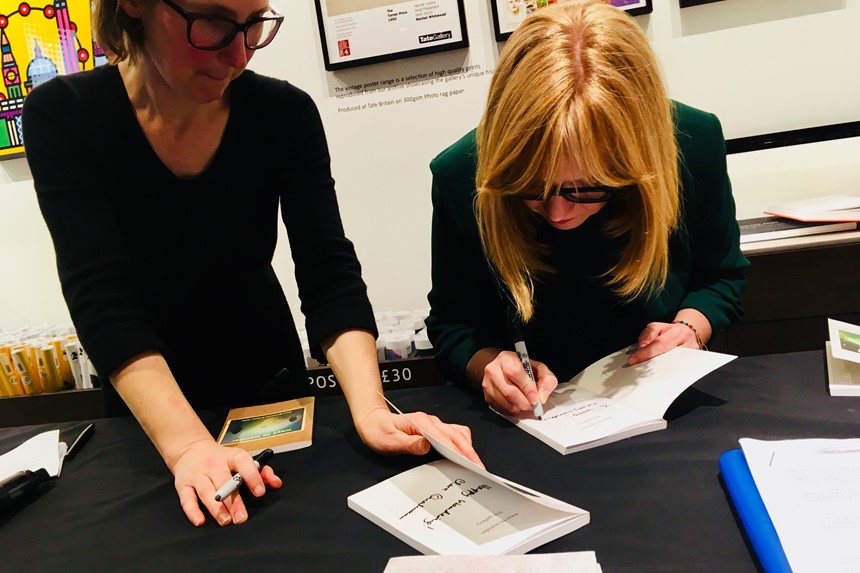

Clare and Claire leading a walking practice in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern

Can you draw on a small handful of the wanders from the book to show their variety?

CQ: Debbie Kent’s kinesthetic walk can be a good one to start with - it’s really easy to use anywhere and it’s about using all of your senses, raising awareness of the surfaces around you and under your feet.

CH: Simone Kenyon and Neill Callaghan’s Wander Score is an experience of walking by closing the eyes, walking backward and moving extremely slowly. Misha Myer’s Wander Score rethinks the idea of home as we sketch landmarks that are both familiar and unfamiliar on a journey. Chris Green asks us to walk radically to experience what is public and what is not. Phil Smith asks the wanderer to look for their name in street signs.

Have you personally enjoyed any particularly rich walks that you’d be happy to share?

CQ: Since the book came out I’ve revisited the ‘Chip Walk’ on a couple of occasions. The artist Blake Morris spent a year walking every instruction in the book, inviting people all over the world to join him (in person or remotely). When he walked the Chip Walk Hilary Ramsden walked it with a group of refugees in Lesvos. Later Hilary and I met and compared our experiences. I had been walking in Hackney, east London, and thinking about the gentrification-led changes in the area that are reflected by the lack of chip shops. Hilary’s walk in Greece made clear the extreme circumstances that so many people are stuck in there; walking miles each day to access food, but also the mutual aid and solidarity groups that have been established to support them. We have also repeated the Chip Walk in Prespes in northern Greece, and Plymouth UK. Each location opens up a new field of connections - the meshworks of people, politics and places that the lens of a simple foodstuff reveals.

CH: All of the Wander Scores in the book are rich wander experiences. I have tried them on my own, with colleagues, and with groups of performance students, and in very different contexts. Clare and I were invited to Tate Modern to run a 5-week summer course entitled Ways to Wander the Gallery. Here we developed a series of workshops, inspired by the book, where participants walked the gallery in different ways to embody the art on display. One participant’s wander became a thrilling adventure, climbing the Turbine Hall as if it was a high-risk sport. The scores in this book are useful for creative writers too when thinking about the relationship between walking and writing. And, on field trips these Wander Scores make for exciting city or rural explorations. The reflective pages in the back of the book enable participants to discuss in critical and creative detail their experiences, but you don’t need to be an artist to enjoy them.

Could these ideas be readily applied to other forms of travel/adventure, like cycling? Are you aware of any such work?

CQ: Yes! Many of these instructions are completely specific to walking, but the practice of creating and following instructions as a creative approach to any kind of journeying is of course possible. Kai Syng Tan’s running work immediately springs to mind.

CH: I returned to mountaineering a few years back, and the instructor taking me on a scramble up the Glyderau expressed a wish to braid a creative experience into his instruction. He was a brilliant teacher helping me to assess risk and apply technical skills, yet he admitted an artistic or imaginative angle to his instruction would open up different experiences and make for new and meaningful conversations with those signed up to walking and climbing courses. If you look at the work of Jonathan Pitches and his book Performing Mountains, it brings Mountain Studies and Performance Studies together for the first time.