Stephen Fabes is a medical doctor with a bad case of wanderlust and no sense of direction. He finally found his way home in 2016 after cycling the length of six continents in a 6-year adventure. We asked him to share what adventure means to him now.

Stephen Fabes is a medical doctor with a bad case of wanderlust and no sense of direction. He finally found his way home in 2016 after cycling the length of six continents in a 6-year adventure. We asked him to share what adventure means to him now.

On a hot, sand-blown day in Turkana, Kenya’s most marginal county, I spotted the impossible. Propped against the side of a thatched hut, there was a loaded touring bicycle. In this roadless desert - with 20 litres of water for company, where trails shifted like the people and livestock - that I had chosen to cycle here myself had seemed hard to figure at times. Turkana had been appropriated as a kind of physical quarantine in the last century when the British had dominion over the land. It’s a hot, thorny, sand-blasted Siberia - not the kind of place that I was expecting to find anyone else on a bike ride.

The stranger’s bicycle looked rather wild as well. Rusted, wrapped in flailing electrical tape and cable ties. I was fascinated: who else was out here too?

I cycled around the world for over six years all told, and yet every so often I’d chance upon some grizzled, rudderless soul who’d been going even longer, someone who begged the question of whether roaming for all those years had been particularly good for them. Their sense of home had faded long ago, and mulishly they went on, chasing that hazy dream of ‘adventure’. Resolve had turned into obsession. Jörg was a bit like that.

‘Slow going, huh?’ he said, scratching his belly and sweat rash.

‘Yeah! How long have you…’

‘Years’ he cut in, bored. ‘I’ll die on my bike’.

I’d have laughed, but he made it sound like a fact.

There was something in Jörg that was hard and a little distant, something I couldn’t identify with. And yet here we were, inching through desert, so maybe we had more in common than sweat rash and grubby clothes. Perhaps we were both seeking the same thing.

The travel writer Tim Cahill joked that an adventure was never an adventure when it was actually taking place, to him, an adventure was only one after the fact, it was ‘physical and emotional discomfort, recollected in tranquillity’.

Roald Amundsen had a different notion in mind: ‘Adventure is just bad planning’, he said, and at times, this felt pretty close to the truth too.

'Adventure is just bad planning, and at times, this felt pretty close to the truth too.'

Stephen cycled across 75 countries covering 53,000 miles.

Camus wondered whether risk must be related somehow: ‘What gives value to travel is fear’ he wrote ‘it breaks down a kind of inner structure we have’. A sense of vulnerability is tied to my own concept of ‘adventure’ I suppose, and it’s never more intense than on the small, wiry roads, through shy towns and wide spaces.

It took me some years to burn out, and when it happened, it was not so dramatic, rather, it happened by degrees. As I meandered around the world, I noticed myself drawn more and more to spare places, where I felt at risk. Remote parts of Myanmar, where landslides were a constant threat. A Mongolian winter, and then an active war zone as I pedalled shiftily into Afghanistan, chasing ‘adventure’, or what I assumed that to be.

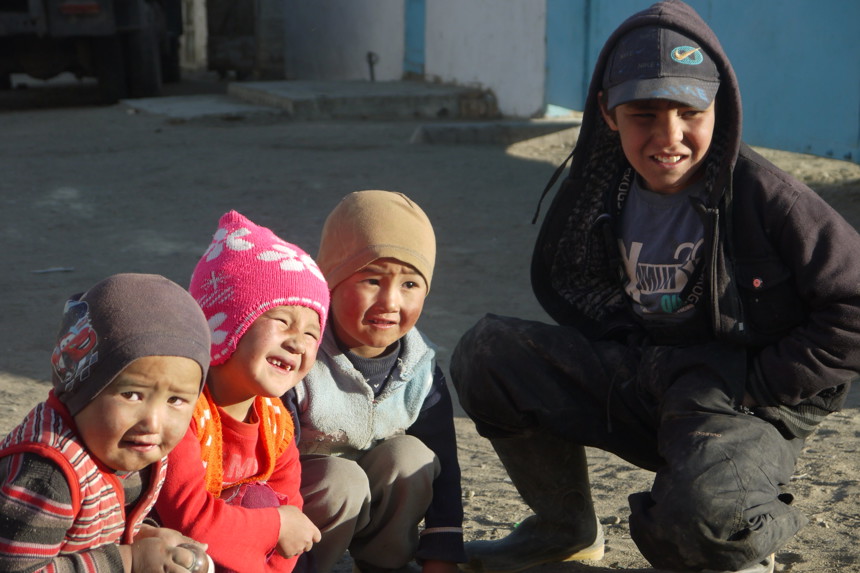

Travel is obsessed with otherness. We yearn for otherworldly landscapes, other cultures to get lost in, other perspectives: a bicycle saddle, a horse back, a rowing boat, a smooth slab of granite, stretching into the abyss. But as time passed, it occurred to me that other forms of adventure were there for the taking too, and they had more to do with commonality and connections.

In Asia, I began visiting medical projects as I rode. I’m an A&E doctor by trade, so at first this was just an opportunity to indulge my own curiosity. Later, I found writing about what I learnt and witnessed along the way gave me a new feeling of purpose. I began to sense that I was on two adventures now, one was the physical ride, the sensory rush, the mud and wind. In parallel, another adventure: to understand something of the forces shaping health, and by proxy, places themselves. This, after all, was how London was best revealed to me, not simply through residing there, but through the NHS, which led me to Londoners of every stripe and gave me a new angle on the city. And for this parallel adventure too, my bicycle did nicely. A travelling cyclist is often invited into homes and communities, where the undercurrents of health and disease can be easier to see.

So, home at long last, what does adventure mean to me now? I can only say that I have a broader, and perhaps a more blurry, definition in mind. I am not so convinced that dusty roads and solitude and risk need to play a part, although of course, they can. To me at least, an adventure is simply a change of tack. It’s following your nose and embracing uncertainty. It’s flipping your view.

'I began visiting medical projects as I rode. I’m an A&E doctor by trade, so at first this was just an opportunity to indulge my own curiosity.'

Stephen’s first book, Signs of Life: to the ends of the earth with a doctor, is launching today, August 6th.

You can pick up a copy on Amazon or an independent bookseller direct from Stephen's website here: www.stephenfabes.com