LIGHT has resonated with people around the world, such that Caroline has been bombarded with messages. “I felt like an ostrich with my head in the sand for many months, because I didn't expect this, and I don't know what to do,” she admits.

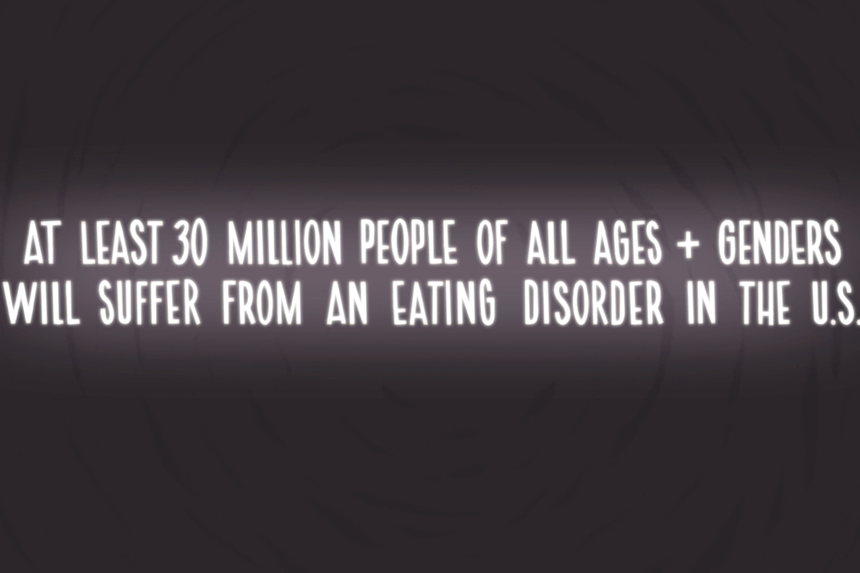

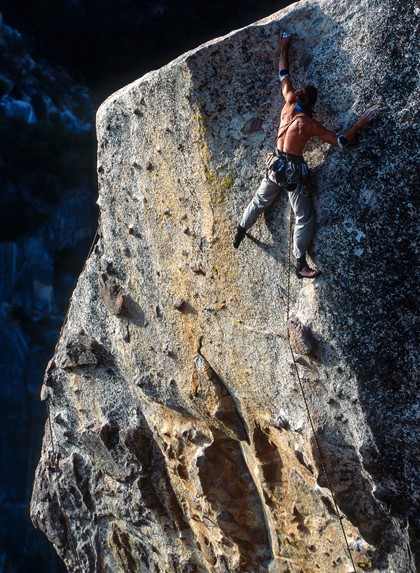

The vast majority of these messages have been thankful, from young to old. “I was at an event where a nine-year-old girl came up and thanked me,” Caroline says. “She had watched it with her parents. She's on a climbing team … She was like, ‘Everybody on my team is struggling with this. Thank you so much.’” At the other end of life’s spectrum, Caroline has also heard from people in their sixties, who have struggled for most of their lives with an eating disorder. Such messages are bittersweet. “Some people don't recover,” Caroline says. “Some people are stuck there forever.”

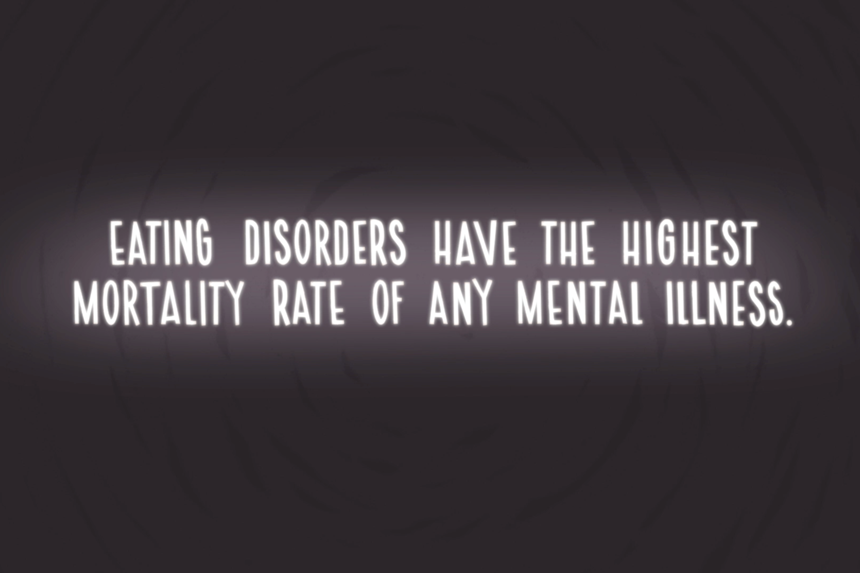

There has also been some denial, and even some criticism that LIGHT shares a scary message. But Caroline respectfully disagrees. “I took that kind of as a compliment,” she says,” because I don't think it's a bad message. I don't think it's a scary message. I think it's scarier when we don't talk about things.”