A growing movement of radical geographers, activists and artists are exploring the risks and possibilities of radical mapping. Our Editor Sam Firman into the world of counter cartography.

A growing movement of radical geographers, activists and artists are exploring the risks and possibilities of radical mapping. Our Editor Sam Firman into the world of counter cartography.

Maps are one of the foundational objects of adventure - landscapes of possibility enticing us to plot a path. Rarely does an adventure not rely on some kind of map, whether a spinning atlas of inspiration, an OS grid charting terrain or an X-marks-the-spot sketch leading us to the treasure. Maps provide information we use and trust.

It is tempting to see maps - except treasure maps, perhaps - as objective representations of how the world really is. But this is misleading. While most maps contain factual elements, every map is a social representation of space: a result of decisions, omissions and conventions with powerful repercussions for how we experience the world.

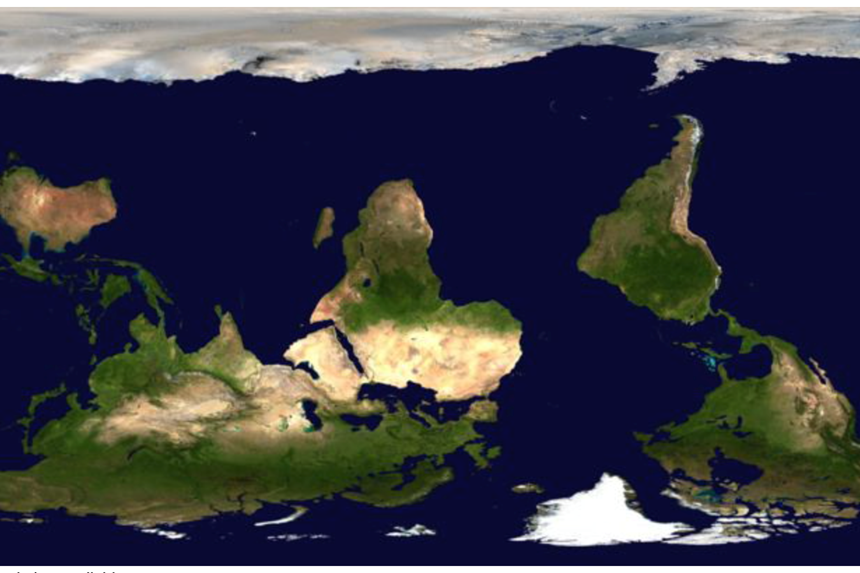

Picture a world map. Is Europe in the middle and the North Pole on top? Created by colonial seafaring powers, this map is in many ways a fiction. Europe is not, in reality, any more central than anywhere else; that we see it this way derives from the location of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London - in other words, from British political power. The ‘Far East’ is a misnomer, too - one that abets the idea of east Asia as somehow ‘oriental’ and exotic. Similarly, my own fascination with Chile is based largely on its enticing location in the southwestern corner of the map. This is subconscious flat Earthery, rife with the risk of bias. A Pacific-centred world map helps expose this.

There is no up or down in space, but today we experience north as up and south as down. The reasons for this are disputed, but it is a relatively recent choice. Over the centuries different cultures have used a range of ‘orientations’ (a word derived from the fact that east - the ‘Orient’ - was used by Christians, including by Columbus, to navigate the world). Northern Hemisphere countries once rarely placed north at the top, because north was where the darkness came from. And early Islamic cultures, which were north of Mecca, favoured south at the top so maps looked ‘up’ at Mecca. Today though, certainly in Western cultures, north is up and south is down. We have also attached values to this formulation - moving up as good, going down as bad - to the extent that it can perversely affect how we value northern and southern places.

A world map with south at the top.

Historically the most popular world-map projection has been the 1567 Mercator projection, the first to account for Earth’s curvature. But this dramatically exaggerates the size of territory at the poles, such that Greenland appears larger than Africa despite being one fourteenth the size. More generally, developed northern hemisphere nations appear enlarged and poorer equatorial nations diminished. A Mercator-corrected world map looks very different.

A Mercator-corrected world map, courtesy of The True Size.

What happens when we play with these conventions, treating maps critically as things to be analysed, deconstructed and remade? At the very least, as the maps above attest, the world feels fresh and unfamiliar. Experiencing regular unfamiliarity thanks to new spatial lenses can help loosen entrenched assumptions and help us reappraise the relevance and prominence of different places as we read, think and travel.

Counter cartography, or countermapping, is a growing practice that poses just this question and seeks practical answers. It is a theoretical and activist method for social change that involves not just reading maps with scepticism, but creating new maps to serve particular political purposes and demands, typically on the behalf of dispossessed social groups. Countermapping recognises the risks embedded in maps, and dares to confront them. “Countermappers refuse to accept conventional cartographic assumptions of the map as an objective representation of the Earth’s surface,” Laurenz Virchow of the German counter cartography collective, kollektiv orangotango, tells me over Zoom. “And at the same time it uses that operability to tell different stories of the world for particular territorial demands and interests of social movements.”

Academically counter cartography emerged in the 1980s as a strand of critical geography: a school of geographic practice paying close attention to the social inequalities of race, gender, sexuality and more. Seminal works like John Brian Harley's Deconstructing the Map (1989) and Denis Wood's The Power of Maps (1992) argued that maps must be read critically as ‘texts’ rather than straightforwardly factual representations of reality. Critical geographers came to understand the importance of reclaiming and democratising mapping: working to turn cartography from an exclusive tool of academic institutions and neocolonial governments into a practical tool for social movements and citizens. Since then, Laurenz says, critical cartography has increasingly become a part of geographic curricula.

But counter cartography as a political tool predates academic debate. The founding example was pioneered by First Nations peoples in Canada in the 1970s. In response to land dispossession by the colonisers, the logic emerged that more Indigenous land had been claimed, and so could be reclaimed, by maps than by guns. Countermapping became an important tool in First Nations’ campaigns for self-determination. The Nunavut Atlas of 1992, for example, helped realise the autonomous Inuit territory of Nunavut, in northern Canada, in 1999.

This success encouraged the dissemination of counter cartography as an anti-oppression tool to other Indigenous groups around the world. The term counter cartography was in fact coined in 1995 by Nancy Peluso, who was working on forest mapping in Kalimantan, Indonesia to describe how the Indigenous Dayak people, who had been managing the forest for centuries, were appropriating the techniques and technologies of state cartography to legitimate their own territorial claims.

'What happens when we play with these conventions, treating maps critically as things to be analysed, deconstructed and remade? At the very least, as the maps above attest, the world feels fresh and unfamiliar.'

If cartography, with its claim to represent truth and conscious and subconscious omissions, is what Laurenz describes with Milan Kundera as “a method of organised forgetting,” these examples show how countermapping can become a method not just for remembering, but for changing society and re-imagining as well as realising desired worlds.

In recent decades critical geographers, artists and activists around the world have developed countermapping into an established craft. Seminal work includes Joaquín Torres' América Invertida, which inverted Latin America; Öyvind Fahlström’s World Map, which mapped the United States’ political expansion after World War Two; Mark Lombardi’s Narrative Structures, sociograms documenting major news events; and, more recently, Trevor Paglen and A. C. Thompson’s Torture Taxi, which investigated CIA rendition flights transporting kidnapped detainees.

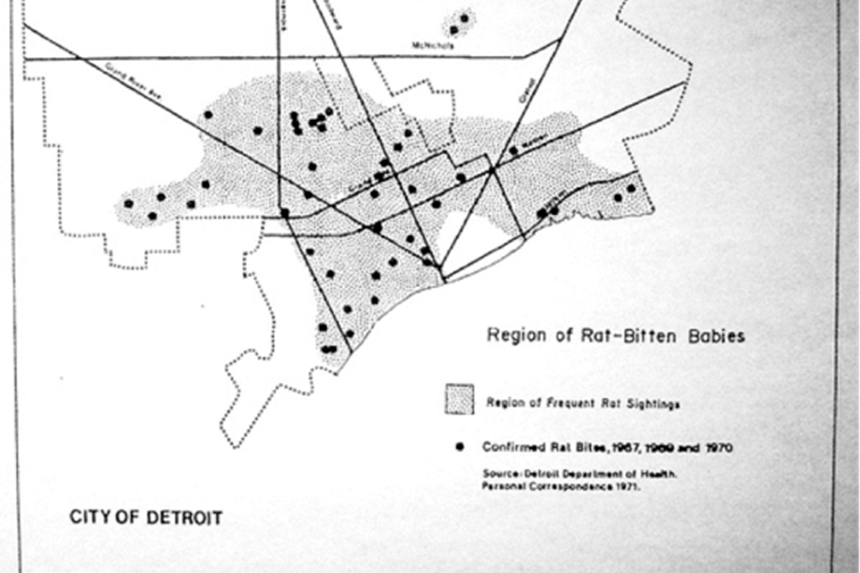

Gwendolyn Warren’s and William Bunge’s 1968 Detroit Geographic Expedition is also widely credited as a pioneering example of community-based radical, participatory cartography. Working alongside local residents - ‘urban explorers’ deciding what data to collect and collecting it - the expedition highlighted stark racial inequalities through maps charting phenomena like regions with lots of rat-bitten babies.

William Bunge and Robert Bordessa, “Region of Rat-Bitten Babies,” The Canadian Alternative (Toronto: York University 1975), p. 326.

Beyond this work, institutional countermapping nodes of theory, practice and publication have emerged, from online resources like Decolonial Atlas, the Bureau d'Études in France and the Counter-Cartographies Collective in the United States to kollektiv orangotango. Argentinian art and research duo Iconoclasistas are also regarded as trailblazers, working with communities on workshops mapping dispossession, precarity, resistance, and diversity and more to encourage the mapping of aspects that are usually excluded from dominant maps.

This evolution has been partly driven by the development and democratisation of Geographic Information System (GIS) technology. Making a map has never been easier, with maps produced and used more than ever. But early optimism among counter cartographers about the possibilities of GIS has been tempered by the realisation that, as with social media and other digital revolutions, democratising processes are countered by the centralisation of resources and ways of working.

Google Maps is the obvious example here. By far the most prominent digital-mapping technology, it offers bewildering and incredibly useful functionality. But Google Maps is a tool of commerce, not political liberation. The integrated ads, branded pins and businesses as landmarks it displays, and the data it mines beneath the surface and sells to companies like Uber and Lyft, subtly normalise a primarily commercial view of our environments - all while generating around $4bn per year, even in a highly “under-monetised” state. Google’s hegemonic hold on digital mapping, all part of a wider mission it sees as virtuous but many do not, is not entirely unlike the mapping hegemony colonial states once held. What might those sorts of maps freed from the interests of commerce look like in a more critical world?

'But Google Maps is a tool of commerce, not political liberation. The integrated ads, branded pins and businesses as landmarks it displays, and the data it mines beneath the surface and sells to companies like Uber and Lyft, subtly normalise a primarily commercial view of our environments.'

This Is Not an Atlas, by kollektiv orangotango, provides some possibilities. The collection is a beautiful, open-source book and homepage telling the story of the evolution of counter cartography, showcasing its possibilities through over 40 global examples and inviting activists and social movements everywhere to add counter cartography to their toolkits. Each chapter includes maps demonstrating a different political function in action, from supporting direct action through making the invisible visible and demonstrating how we all experience spaces differently.

Compelling examples abound in the book, like the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP) in San Francisco. The AEMP uses geospatial data collection, visualisation and analysis to map and ultimately alter the relationships between capitalism, the tech industry, real-estate speculation and evictions of low-income and Black communities in gentrification processes. As well as working with data, the AEMP’s Narratives of Displacement and Resistance project also embeds oral history and video work. All of its work - including its recent Counterpoints: A San Francisco Bay Area Atlas of Displacement & Resistance - is closely aligned with local people, community partners, campaigns and events contributing to collective forms of resistance and movement building.

Berlin Besetzt is an interactive digital map of Berlin squats between 1970 and the present day. Squats have been integral to political struggles in Berlin over the past 50 years, and Berlin Besetzt uses countermapping to chart this history and show how social movements have and can be successful using spatial tactics. Laurenz, who lives in Berlin, says the project transformed his own view of the city, helping him better appreciate its political geographies since the map chooses to view the city as a place of ongoing political struggle and change, not just a site of commerce, tourist spots and transport.

'The map chooses to view the city as a place of ongoing political struggle and change, not just a site of commerce, tourist spots and transport.'

This Is Not an Atlas doesn’t see countermapping as a solution - “the map can never be the territory,” Laurenz quotes, paraphrasing Alfred Korzybski - but a tool and a process that can problematise everyday life, open up new possibilities and help groups work towards political goals. “A critique does not consist in saying that things aren't good the way they are,” he continues, quoting Michel Foucault: “it consists in seeing on just what type of assumptions, of familiar notions, of established and unexamined ways of thinking the accepted practices are based... To do criticism is to make harder those acts which are now too easy.”

Selecting maps for This Is Not an Atlas was challenging, with the line between map and counter map often blurry. The faultline generally sees counter maps support local communities, especially those excluded or disadvantaged. But beyond this there is no clear political dividing line. "The fact that groups across the political spectrum create these sorts of maps illustrates that countermapping itself is not necessarily politically progressive,” wrote Dennis Wood - quoted in the introduction to This Is Not an Atlas - “but that geographical imaginations are important sites of struggle." Thinking about the environments we live in and explore need not be party political.

The key point, Laurenz concurs, is to “always have to read maps critically.” Even countermapping with the best intentions can be counterproductive. Laurenz recalls a well intentioned proposal to map occupied houses across southern Europe. The proposal created a backlash because instead of helping connect activist networks, it would have helped authorities identify and evict activists and other squatters.

'The fact that groups across the political spectrum create these sorts of maps illustrates that countermapping itself is not necessarily politically progressive, but that geographical imaginations are important sites of struggle.'

Countermapping is not a tool for experts. It is open to all of us - a key tenet of the countermapping movement. Accordingly, This Is Not an Atlas contains a section of three chapters outlining how to design counter maps and, whatever the nature of the project, ensure solidarity with relevant social groups.

The question of how we might counter map our own place(s) is a provocative one. It is also an adventurous one. What could be more adventurous than countermapping: plotting the overlooked, the unknown and the desired on a map? But: “Deconstructing maps can really be an adventure,” Laurenz says. “It really helps to uncover social power relations in discourses. It’s adventurous because it really demands from you to doubt your everyday life and be attentive about the way everyday life is communicated (in maps).”

'What could be more adventurous than countermapping: plotting the overlooked, the unknown and the desired on a map?'

What’s more, counter cartography is not only the act of making physical or digital maps. It also means reading and using maps in new ways as we explore. Laurenz raises the Situationists of the 1960s, a movement of social revolutionaries who used psychogeography as one tool to understand and subvert how capitalist environments affected people’s experiences and emotions. One of their methods was to walk the streets of Paris using a map of a different city.

Taken further, countermapping might involve exploring without a map, but with some new mental map helping us navigate differently. Indeed, it seems odd that the notion of ‘going into the unknown’ - how adventure is often framed - is frequently guided by a tool purporting to remove much of that unknown. Some of these techniques, in Laurenz’ words, might even have the potential to “redefine our geographic imaginations.”

The question of how to redefine our geographic imagination as an adventure community feels like a good rallying cry. The possibilities feel endless. What if climbers mapped empowering and offensive route names? Or ramblers mapped trespassing activity? What if they could help to remove barriers to outdoor activities and highlight that the outdoors is for all of us? These maps would surely contribute powerfully to important conversations. Whatever our place in the adventure world, and wherever we travel, the ability to read maps and our environments critically, and to think about how the places we cherish might be countermapped, should always be in our rucksack.

But even without our rucksacks on, the spirit of radical cartographers such as Gwendolyn Warren and William Bunge might inspire us to re-discover the places of our everyday lives. Discussing the forgotten histories and silenced perspectives in our neighbourhoods with people next door is every bit the adventure - adventure not driven by a desire to discover the unknown far away, but a commitment to re-encounter (un)known people and places nearby. An adventure that seeks to deepen our connections close by helps us create a “more human dwelling world.”

You can contact Laurenz and the rest of kollektiv orangotango at info@orangotango.info or www.orangotango.info.