Storytelling for Conservation

Those plaques you read sealed to the glass of the tigers’ enclosure at the zoo? They’re stories. The ones telling you who Budi’s parents are, where he was born and how much he weighed are life stories, giving character to captive animals.

I, myself, have used storytelling to drive conservation efforts. We are so much better at caring about one creature we know than about thousands of unnamed, faceless lives. Storytelling in conservation is nothing new. But like everything else in our world over these last few months, it has changed.

Conservation in lockdown

COVID-19 is clearly wreaking havoc on humans, but it is also making life even more perilous for endangered species. While urban wildlife has been finding respite in quieter cities, fauna that find their homes in zoos, protected marine areas, national parks and conservation reserves around the world are actually missing our presence.

Zoos have worked hard to change their morally questionable reputation into one of pivotal figures in the fight for animal survival and welfare. They fund and conduct scientific research, sponsor and run conservation programmes overseas and provide much needed education about the importance of wildlife, both in animals’ host and home countries.

Zoos have made recent headlines in the UK for their effervescent lobbying to open up with other non-essential businesses on June 14th. But now only allowed to open at limited capacity (across the country, at an average of about one fifth), they are still appealing for help. David Attenborough has even announced a campaign to raise £25m for the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) to plug their income gap. “Put bluntly,” he says, “ this institution is now, itself, at risk of extinction.”

Without visitor income, many of ZSL’s programmes have been halted. Without tourists, fears of mass-euthanisia are growing in popular travel destinations like Indonesia and Thailand, where an industry responsible for tens of thousands of animals relies heavily on people visiting the sanctuaries and national parks that feed them.

Lockdown has not just meant a loss of income here. Food and supply chains are disrupted, human-wildlife conflict has escalated and bushmeat poaching is increasing. Many conservation organisations are having to suspend some of their care, unable to pay their rangers, and rely entirely on donations.

It is not just tourist attractions feeling these pains. Tracking/monitoring initiatives, breeding programmes and anti-poaching works also usually fall under similar funding schemes, and have been equally hit by the pressures of lockdown. These programmes cannot just hibernate; the animals aren’t going anywhere just because humans have locked down.

Attenborough is not alone in recognising this desperate need to plug an expanding income gap. Nor is he alone in answering the call. In place of spending money on travelling abroad this year, people are raising money for these animal homes to keep them afloat from home in the UK.

'Tracking/monitoring initiatives, breeding programmes and anti-poaching works also usually fall under similar funding schemes, and have been equally hit by the pressures of lockdown. These programmes cannot just hibernate; the animals aren’t going anywhere just because humans have locked down.'

Virtual conservation adventures

Adventure is often harnessed as a mechanism for conservation and fundraising. Visiting conservation projects is often an adventure, as are the fundraising stories we are familiar with, like climbing Mount Kilimanjaro or running the London Marathon. During lockdown, though, just as the conservation story is changing, these adventurous efforts are morphing into home-based, virtual appeals.

Having been easily swept into some questionable elephant ‘sanctuaries’ as a teen, it was clear to me that the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) was different: a pioneering, research-driven, welfare-focused organisation that fully trains all its volunteers and keeps field groups small and a good distance from the animals. The SLWCS has a large range to look after, and was hit hard by the lockdown in March.

Like me, Mags Nixon visited in 2019. She had been there in part for love, experience and enjoyment, and in part to help spread their activities through her Instagram following and blog. “They’re just an extraordinary organisation,” she said. “I was just so inspired by their initiatives. They have such a clever way of identifying the root problems and working with the local people.”

'It was clear to me that the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) was different: a pioneering, research-driven, welfare-focused organisation that fully trains all its volunteers and keeps field groups small and a good distance from the animals.'

Mags knows the potential of harnessing the power of a large following, so when the crisis hit, she knew what SLWCS had to do: “I reached out to Ravi (the SLWCS President) and said ‘Look, you’ve got a whole database of volunteers you could tap into for help’” - the large list of people who have served in the park and care so much about the work being done there.

The SLWCS has managed to stay afloat, partly by launching an e-volunteering programme, as of June 29th, where full training is provided in tasks including fundraising, content creation and virtual field research.

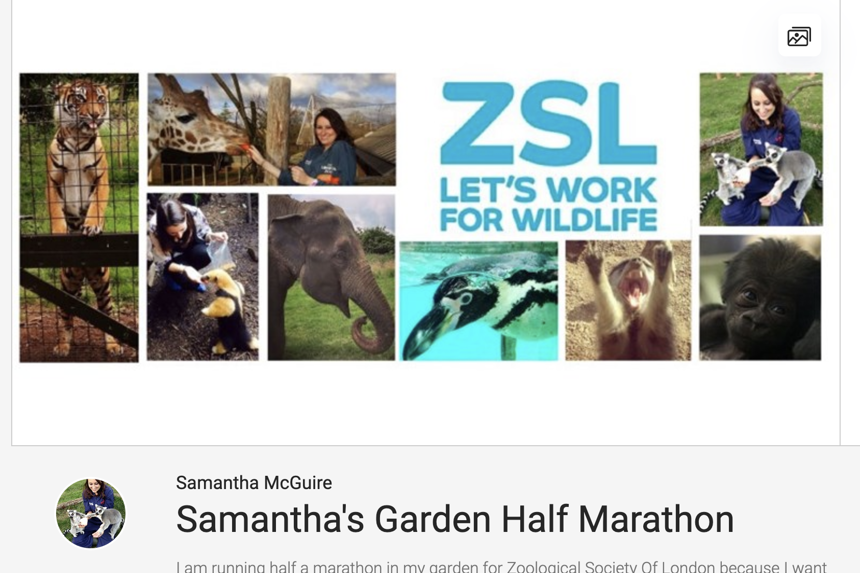

Sam McGuire has worked as a fundraiser for ZSL, so immediately recognised the sharp and painful impact the pandemic would have on the Society’s research and conservation work. For many, though, wildlife are now at the bottom of the list of what is ‘essential’. “It's quite a difficult financial time for everyone,” says Sam, “so I found it quite difficult to fundraise this time.”

Searching for a way to raise money from home, Sam had an idea. “I’d been training for a marathon anyway,” she explains, “but obviously that got cancelled, so I decided to sort of put the two together and just do it in my garden.” It took twice as long, given her garden is quite tight, so she wasn’t able to fully stretch it out. A full marathon understandable became a half marathon. “It felt like travel sickness. I think I’ve done over 4000 laps!”

Tusk, which CEO and Founder Charlie says “operates like a hedge-fund manager,” partners with conservation programmes on the ground in home countries to funnel funds into developing and growing those programmes and promoting them around the world. Tusk supports 45 projects in 20 countries, but “the tap has been turned off overnight.”

To respond to this continuing and growing need, Tusk held a very successful virtual marathon on June 27th to replace the main event, which is usually the centrepiece of their fundraising year.

“One good thing I really hope might come out of all of this,” Charlie says, “is the global realisation that we are so much more connected to the natural world than we have come to understand. In man’s arrogance, we’ve become somewhat disconnected. It’s all interlinked, and wildlife is as important as anything else. We simply have to do a lot more to protect functioning ecosystems and landscapes.”

A new story for conservation?

This rise in virtual conservation volunteering and a technology-assisted shift to lower-contact wildlife activities for tourists may actually lead to better lives for animals in captivity. People are still eager to give, and many fears for wildlife have been held off so far. But the holes and flaws of a tourism-based captive conservation system have been revealed by a paused economy and global pandemic.

Maybe what we will learn from this is that conservation dependent on wealthy, Western tourism into a range of countries is not sustainable, or just. A conservation movement must not just include, but be driven by the people living with the animals in home countries. Animals must have inherent value, supported by the global population. We all depend on the great diversity of this planet, not only to keep us safe from the threat of more zoonotic diseases, but to live full, rich lives. This is another area we must redesign to ensure biodiversity and ecosystem survival, or face much more dire consequences than those to have reared their heads during COVID-19.

If you would like to learn more about what wildlife faces during COVID-19, what is going on for captive animals around the world and how we are trying to better understand how to care for them, check out my podcast episode with veterinary wildlife researcher, Dr Lisa Yon.

Keep exploring