Miles was already pondering the possibility of bringing backcountry-style hiking into urban spaces when he walked San Francisco’s 17-mile Crosstown Trail, which dissects the city from the northwest to southeast. Though initiated by the city council, it was completed by a coalition of volunteers impatient with persistent delays, complete with written directions and free maps. Inspired by his experience, and the trail’s roots, Miles returned to Boston and began plotting.

But how to begin?

Urban trail development is logistically simpler than backcountry trail building in that the building is already done; the task is simply to curate and promote. But proposing a trail through a landscape dense with millions of potential stakeholders poses other challenges. Would it not be presumptuous to single-handedly curate a route that, intentionally or not, may seem like a definitive tour?

The first challenge was therefore to decide between recruiting collaborators and proceeding collectively or forging ahead with a prototype before inviting feedback and input. “In my experience, the difficulty you run into with the former approach, while more holistic in the long run, and reflecting a community vision, is that nothing happens for a long time,” Miles says. “I wanted to act on this idea while the energy and excitement were still very fresh.”

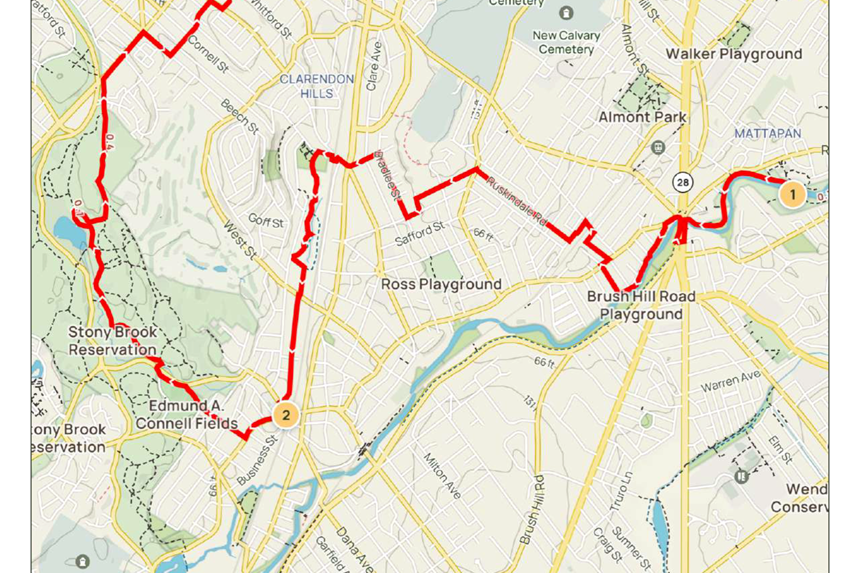

With some reservations, Miles began plotting a path connecting Boston’s abundant green spaces. Many days of GPS investigation and on-the-ground corroboration later (he plans to publish an urban trail-building guide to the WCT website in late 2023), he published the first maps and started offering guided test hikes in June 2022. These soon reached capacity, and led to connections and suggestions that have improved the trail. Miles now works with a team of trail developers – including Matthew Broude, Jules Murdza, and Patrick Maguire – and wider stakeholders, including supportive councillor Kendra Lara.

The approach seems to have paid off. Though Miles expected pushback against his initial decision to act alone, he thinks his openness to support and suggestions, as well as the novelty of the project, have kept this to a minimum. The most notable opposition, he says, has taken the predictable form of NIMBYism – specifically the removal of trail signage.

Miles has also made it very clear that his aim is not to establish the One True Boston Trail, in a city which already enjoys the seven-mile Emerald Necklace and plenty of trail-threaded green spaces. Rather, he hopes to “gin up enough community interest in urban trails in general that more trails can take root in the city of Boston in the future. Possibly more trails like this, designed by community organisations first and foremost. Possibly even trails that are shepherded by the city in some way.”