Nik Elvy knows, from her personal experiences and her work, that the outdoors is not free or accessible to all. Here she writes about the work still to be done to heed this.

Nik Elvy knows, from her personal experiences and her work, that the outdoors is not free or accessible to all. Here she writes about the work still to be done to heed this.

I was an adventurous kid. I loved jumping off stuff, going exploring and seeking out tiny adventures. I did not grow up in an idyllic countryside setting, however. I grew up jumping off of the flat-roofed garages of the council estate where we lived.

The outdoors can be heavily romanticised, and there is a widely held belief that it is free. But it is not free. I know this from my own childhood experiences, from the work that I do now as an outdoor leader and from my current PhD research.

'The outdoors can be heavily romanticised, and there is a widely held belief that it is free. But it is not free.'

Access to the outdoors is something I have been concerned about for a long time. Three years ago I wrote:

“The outdoors as privilege is on my mind a lot at the moment.

I am part of a gang of outdoorsy types who believes that the outdoors is good for you. I believe that it can be beneficial for health and education. I believe that it is beneficial for the health and education of not only individuals, but also communities and ultimately our planet.

What's bugging me though is that I know people who can't access it. I know people who can't drive to it, can't get the appropriate kit to be in it or who are having local green spaces taken away, bought and developed.

Even the common outdoor mantra "There's no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing" is problematic.”

This was pre-Covid. Now, following the restrictions placed on local outdoor public spaces in 2020, at the start of the pandemic, we understand even more that access to the outdoors is not equitable. Some had fantastic local green spaces or even their own gardens to enjoy, whereas others did not have a suitable outdoor space within walking distance, and many had no garden in which to even sit in the sun.

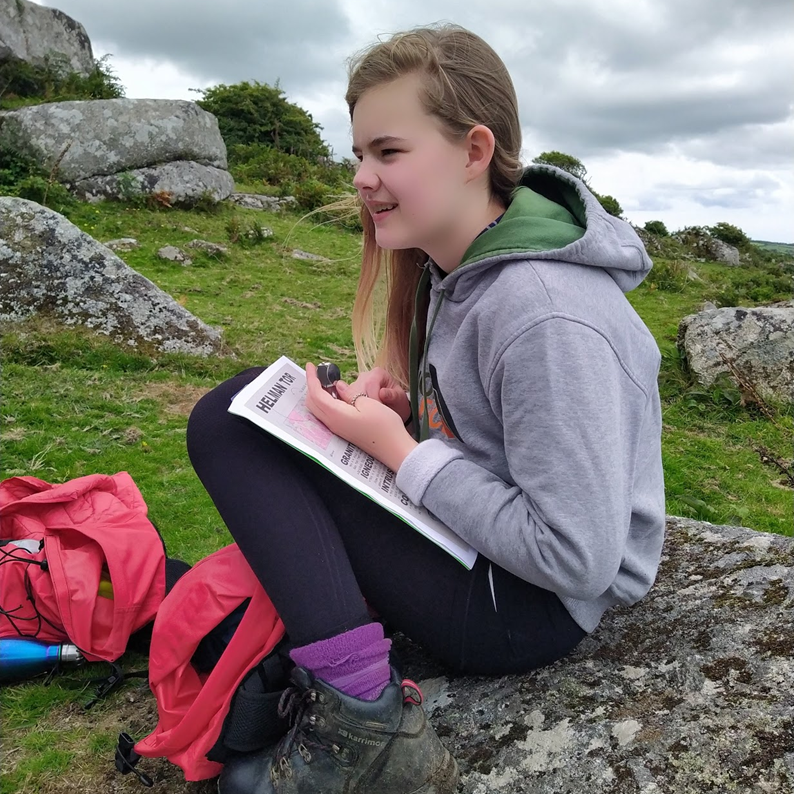

Photos of Curious School of the Wild, courtesy of Nik Elvy

More research is coming out all the time exploring the benefits of the outdoors on our physical, mental and social health, and yet I know first-hand that many people still cannot access it. There are some concerns that this research is often completed with participants who already access the outdoors, and that in reality it is hard for us to use it to understand why some people can’t access green and blue spaces for recreation, play, learning and health.

People on low incomes and experiencing poverty often find it difficult to get outdoors. A lack of resources can be a major barrier. I see this in my everyday outdoor practice, but it is also backed up by the Natural England’s The People and Nature Survey 2020, which found that people with lower incomes are less likely to access natural environments and outdoor spaces.

Firstly, access is diminished when there are fewer natural spaces close to where people live, or a lack of transport options to natural spaces further away. Kit and clothing can also be an issue. I know that many school children, for example, only have their school shoes, and may not have an appropriate outdoor coat or any coat at all. Even being asked to provide wellies, a coat and a change of clothes for outdoor learning sessions in school can be a massive problem for many families who do not have enough resources.

Marcus Rashford did so much to highlight the problems for families in poverty who do not have enough food. Being hungry has a huge impact on how a person feels and behaves outdoors, and even whether they are safe. The Children’s Poverty Action group highlighted in their research about young people and food poverty that a lack of food can also mean a lack of social interaction. In our work at Curious School of the Wild, we understand this. We know that food can be a ticket to participation, and without it people may not join in, so we make sure we provide food as a default in all of our work. We are well known for providing second breakfasts, for example. I have written and made videos about the benefits and joys of a second breakfast, especially when you are not sure that everyone who is outdoors with you had their first breakfast. We call this kind of approach ‘poverty proofing’.

'Marcus Rashford did so much to highlight the problems for families in poverty who do not have enough food. Being hungry has a huge impact on how a person feels and behaves outdoors, and even whether they are safe.'

As a social enterprise, Curious School of the Wild aims to poverty proof the outdoors and outdoor learning. Firstly this means poverty-proofing our own day-to-day practice, and then it means making sure that we talk about poverty proofing and inform people where we can. Although it is understood that access to the outdoors has been tough for many marginalised groups, and we have seen this situation slowly improve and fantastic role models emerge, the same is not happening for people on low incomes and in poverty. It is hard if not impossible to find a great outdoor role model who grew up or lives in poverty.

Part of the reason for this is, beyond a lack of resources, is the stigma attached to poverty. I was recently asked to be interviewed about my lockdown experience for a newspaper article. I am a single parent of three children and still manage on a low income. I discussed how lockdown had worsened the stress of living on a low income, as I was also unable to work outdoors with our groups for the majority of the year. After publication, someone tracked me down and wrote on my Facebook wall: “Stop enjoying yourself outdoors and get a job so that you can feed yourselves properly.” As upsetting as this could have been, it was a reminder that for some people, the perception of the outdoors is that it is not really available if you are struggling on a low income as you should always be working harder or looking for work to earn more money to live. This view of the outdoors is that the outdoors is for leisure, and leisure is really not for those who should be focused on improving their financial circumstances.

Photo of Curious School of the Wild, courtesy of Nik Elvy

'For some people, the perception of the outdoors is that it is not really available if you are struggling on a low income as you should always be working harder or looking for work to earn more money to live.'

Poverty propaganda in the mainstream media helps perpetuate the idea that those on low incomes are lazy and work shy, fuelling the belief that being outdoors on a low income represents shirking or anti-social behaviour. These beliefs stand in direct conflict with research that recommends getting into the great outdoors for better physical and mental health or educational outcomes.

The stigma attached to poverty and low incomes begins early in childhood. When children make dens in parent-funded woodland sessions, their play is valued, encouraged and understood as a part of their development. The same natural play on a housing estate can be viewed as anti-social behaviour, and children’s dens are dismantled and disposed of.

There is obviously much work to be done. We have started to do what we can in our tiny corner of the world, and other outdoor organisations are also beginning to understand the importance of poverty proofing the outdoors and working to make it not just accessible, but welcoming. A great example is the The Wave Project.

What is crystal clear to me from my own experiences growing up in poverty, from still living on a low income, from my work with communities outdoors and from my research is that people and children on low incomes experience the outdoors differently to those who are more financially comfortable.