Any definition of adventure includes 'the exploration of places in new ways'. This attempt to experience places with a fresh perspective, and the relationship between people and places more generally, drives Jennie Savage’s artistic work. As the UK slowly emerges into the post-lockdown world, we were eager to learn from her approach.

“I've always been interested in storytelling and how narrative constructs experience,” she says over Zoom during the lockdown. She is interested in “the stories that emerge from somewhere - either mythical, or urban myth or simply factual.”

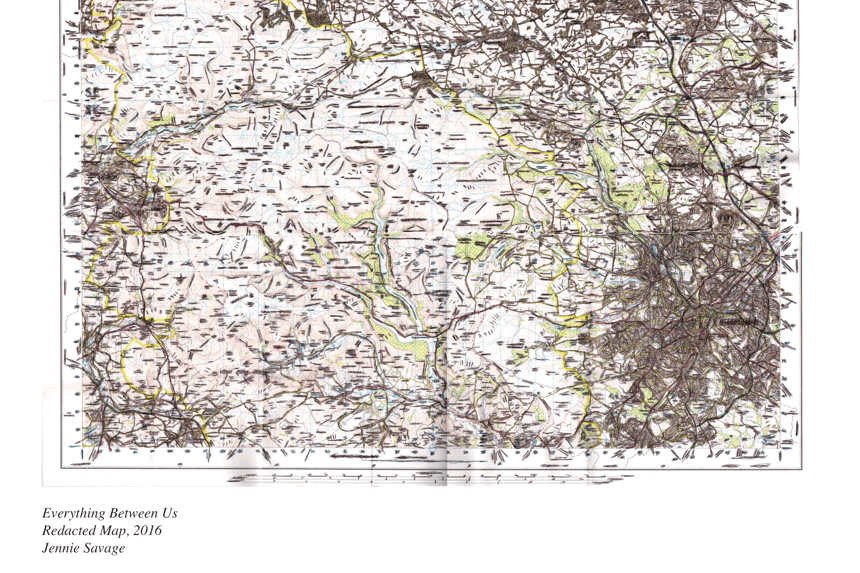

Jennie uses this curiosity to actively experiment with ways to tell new stories about places, and explore them in new ways. “At university I was making a lot of work with maps,” she continues. “It started off with, ‘How do you transcribe a place through drawing a map?’” Her interest then grew into how maps can be used to refuse certain narratives about a place. “How can you build that into a map?”

We are largely dependent on maps for getting around. For most of us this means mapping apps to prioritise efficiency. But what do we lose in following these algorithmic routes? Confined as we are to our homes - the places we know best - this seems an apt time to creatively address this question.

One of Jennie’s proposals here is to get lost, or at least to relinquish some control. The possibilities of getting lost inspired her Guide to Getting Lost: an audio walking tour that feeds the listener randomised directions, as well as the background soundscape - people talking, traffic - of wherever the tour was recorded.

“I was interested in how somebody could walk through familiar landscapes and feel disorientated,” she explains. Her aim was to make a “fictional landscape that people could walk through” that blends their physical environment with novel directions and sensory inputs “A lot of the projects I've done contain this idea: how can you make something that's very familiar seem strange?”

One consequence of the Guide to Getting Lost is that it confronts people with choices about whether to travel, even trespass, through certain areas. “The aim was also to get people to question their own sense of where they belong in relation to private property, or open space or the right to roam.”

'A lot of the projects I've done contain this idea: how can you make something that's very familiar seems strange?'

This concern with how our lived environments are changing, often through private developments that prioritise profit over the concerns of residents and local citizens, permeates Jennie’s other projects.

“For various personal reasons I ended up moving back to the village where I grew up, and I was quite resentful of it” Jennie says. “I'd always kind of grappled with the complete absence of narrative here.”

Her response, in collaboration with Edgework, was a project called That Which Flows From This. The intention was to explore the village anew, using a psychogeographical approach - something popularised in the UK by Will Self’s columns, but conceived by French philosopher Guy Debord as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals."

“One of the first things I did was try and navigate the whole village using only its alleyways,” says Jennie, pointing to the playful methods that can result. “Each day I started to walk with a different sense of purpose and a different way of exploring, and through that a number of narratives started to emerge.”

How might our relationships with places change with such a playful approach? The outcomes might be surprising. In Jennie’s case her exploration led her to a new development planned in the village. “I ended up looking at this development, talking to people that were involved in trying to resist it and organising this protest, with people marching around with placards!”

'Each day I started to walk with a different sense of purpose and a different way of exploring, and through that a number of narratives started to emerge.'

Photos from That Which Flows From This

Beyond getting lost, how can we cultivate a similar spontaneity? The answer may be simple: walking. Or, a particular type of walking.

“A really creative way of approaching walking, I think, is to sort of be alive to what you're looking at and thinking about … I think it was Thoreau who said you should treat a walk like an adventure, and it's about your approach rather than anything external.”

We can learn this perspective, she argues, from other sources too. “I remember when I was doing my [art] foundation course, I had this tutor who said, ‘You could spend the rest of your life painting this glass, and it could be endlessly fascinating.’ That's really stuck with me, and informed my approach to a lot of things … I mean, certainly in this lockdown situation.”

In one sense the lockdown seems to have made it challenging to find excitement and adventure. Jennie’s art, though, and her approach to experiencing places, can help us to find more adventure in the places we live, particularly under these circumstances.

“I've really fallen in love with being here now,” she says towards the end of our conversation, “because [the village] is operating completely differently. People are using this place differently … there's hardly any traffic on the roads, and suddenly there's wildlife and nature literally coming in.”

Reading and recommendations

- Walking, by Henry David Thoreau: a meditation on the joys of long-afternoon walks, and argument for wild spaces and an adventurous mindset. Jennie referenced this book as an influence on her thinking about walking.

- The City & City, by China Miéville: an extremely creative novel, ostensibly about a murder invesitgation but really about place. The underlying premise is that two overlapping cities are divided not by physical barriers, but a deeply embedded psychological prohibition on citizens in either city even being aware of citizens in the other.

- Wanderlust, by Rebecca Solnit: A history of the power and potential of walking, in all its forms. Jennie has used this book with students. I have just started it, and within ten pages have already learned new perspectives on walking.

Keep exploring